How the University of Florida Built a Thriving Math Modeling Program

When the University of Florida (UF) launched its first Mathematical Contest in Modeling (MCM)® and Interdisciplinary Contest in Modeling (ICM)® teams in 2020, only three groups of students were willing to give it a try. Five years later, the program has grown to seven full teams, with undergraduates lining up to tackle real-world problems in just 99 hours.

That growth is the result of a dedicated group of faculty and graduate mentors who built a supportive structure around the contests:

- Dr. Tracy Stepien, Associate Professor of Mathematics

- Dr. Youngmin Park, Assistant Professor of Mathematics

- Graduate student mentors Kyle Adams, Abhiram Hegade, and Hemaho Beaugard Taboe

Together, they’ve created a thriving community of math modeling at UF.

From One Professor’s Experience to a Campus-Wide Program

Dr. Stepien knows firsthand how powerful the contest experience can be. As an undergraduate, she competed in the MCM and was part of an Outstanding Winner team.

“It definitely played a huge role in why I went to graduate school and why I wanted to do mathematical modeling as a career,” Dr. Stepien recalled. “When I joined UF, I knew I wanted to give that same opportunity to my students.”

She kicked things off with just three teams and some informal training. Since then, the program has steadily grown, not just in numbers, but in the support system wrapped around the students.

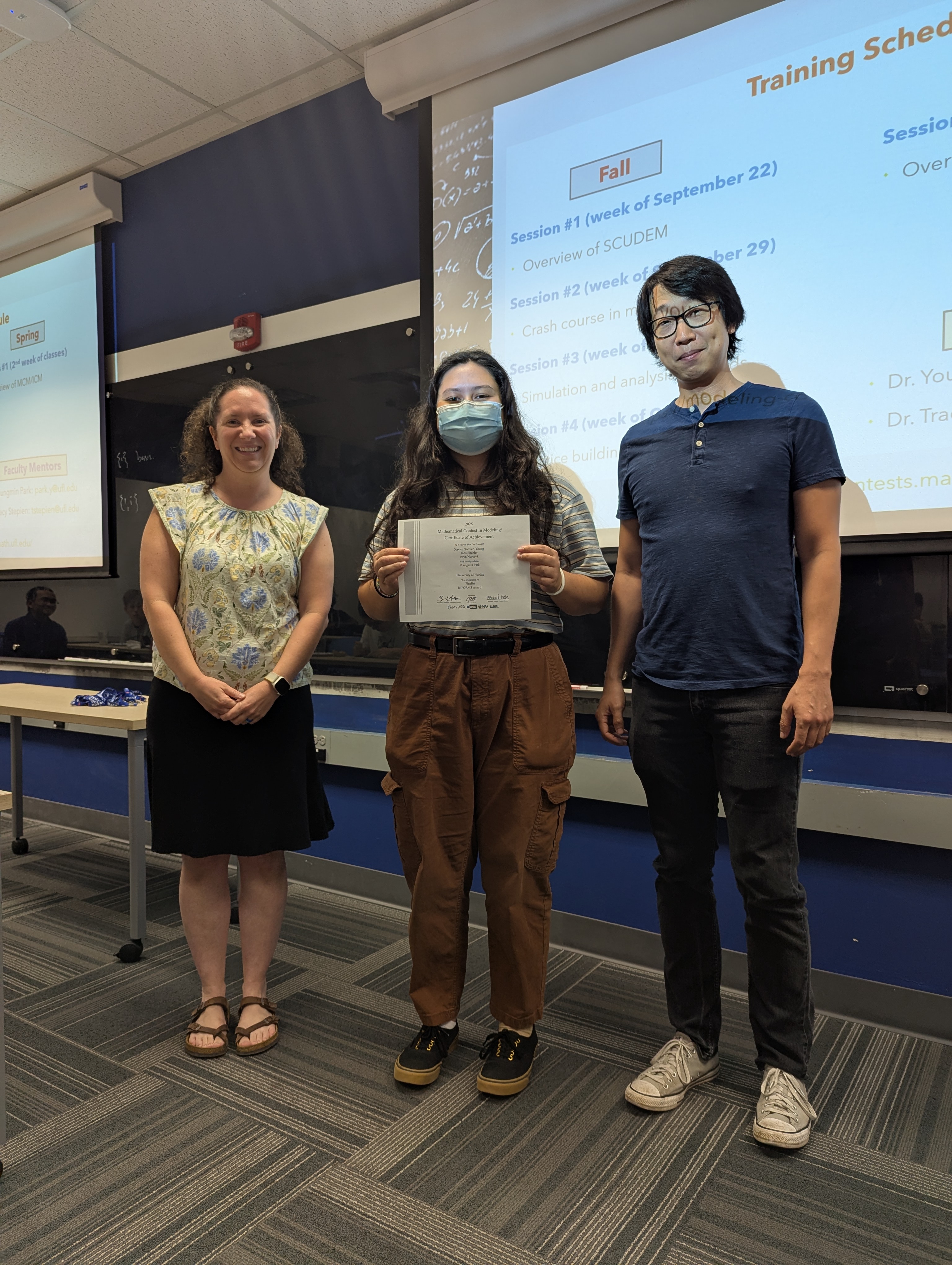

Drs. Stepien and Park with one of the members of the 2025 MCM Finalist team.

Photo credit: Margaret Somers

Training Students Who Are New to Math Modeling

A lot of students come to UF without any background in math modeling. To get them ready, the team puts on a four-week training series each fall:

Week 1: Contest Overview

Dr. Stepien introduces the structure of the contest, the types of problems, and a recommended day-by-day plan for the 99 hours.

Week 2: Intro to Modeling

Taboe walks students through a sample problem, showing how to frame research questions, build a model, and analyze simulations.

“I take one of our papers and go through every step. How we get the problem, how we formulate the research questions, and how we analyze the model and simulations,” Taboe explained. “I also show them the tools available and let them know we’re here to help.”

Week 3: Computational Methods

Dr. Park demonstrates coding basics using Python and SciPy. “I started with the basic SIR model and showed students how to integrate it in time,” he said. “Just changing parameters and conditions helped them see how models behave.”

Week 4: Practice Session

Graduate mentors lead teams through a practice problem to simulate what it feels like on the first day of the contest and how to plan an approach.

“Even when teams hadn’t looked at the problem I sent them in advance, it was still useful,” said Adams. “They got to see what it’s like to open the problem statement for the first time and figure out how to start.”

The Role of Mentorship

Every team works with a graduate student mentor who guides the team through the content preparation process by checking in with them, offering guidance, and helping them navigate challenges along the way. Faculty take care of the logistics and big-picture oversight, while the grad mentors are the ones giving students that one-on-one support to prepare the teams for the contest.

The mentors are there to ask questions, share strategies they’ve seen work, and really help students find their own way forward as they prepare for the contest. “I thought I didn’t have enough experience to be helpful,” Adams admitted. “But just asking questions, like ‘what if this happened?’ was enough to guide teamwork. It’s really fun.”

Some of the Common Challenges Students Face

Like any competition, the MCM/ICM comes with hurdles. “Students often struggle with simulations,” said Taboe. “I share simple examples and code in MATLAB or Python.”

For teams without returning participants, the hardest part is often just knowing where to begin. “The biggest issue was trouble with starting,” noted Hegade. “When no one had competed before, it took longer for teams to figure out how to approach the problem.” To make sure skills are balanced, students fill out a quick form about their skills in writing, modeling, and coding. Dr. Stepien uses that information to build well-rounded teams.

Why Students Keep Participating

The problems that students take on in MCM/ICM don’t look anything like textbook exercises. They’re open-ended and rooted in real-world systems. “The problems are so different from what they see in the classroom,” Dr. Stepien explained. “Students enjoy the challenge, and many come back because they want to do even better the next time.”

Some students have even used the contest as a springboard to research. “One student liked the contest so much that he asked for more resources,” said Adams. “He’s now in my research group.”

2025 Spring Celebration with faculty mentors, grad student mentors, and undergraduate participants (in MCM and SCUDEM) from left to right.

Photo credit: Margaret Somers

Building a Culture Around Modeling

The UF team makes sure students’ work is celebrated. News articles are published through the Department of Mathematics or College of Liberal Arts and Sciences highlighting teams. At the end of the spring semester, teams are recognized during the Department of Mathematics Spring Celebration. Students are encouraged to present at the Undergraduate Mathematics Research Symposium.

“We always try to get a news article written up,” Dr. Stepien said. “We invite all of our teams to the department celebration, and we encourage them to present at the research symposium.”

The group also maintains a UF Modeling Contests website that archives modeling resources, past participants, and media coverage. “Other faculty at UF, and even at other universities, have reached out after finding the site,” Dr. Stepien added. “It’s become a way to build community and share resources.”

Advice for Other Universities

The University of Florida’s story offers a path for other institutions that want to start a similar program:

- Start small. Even a single team can grow into a thriving program.

- Offer training. A few sessions can give students the confidence to jump in.

- Leverage mentors. Graduate students or advanced undergrads can provide invaluable support.

- Celebrate results. Public recognition builds momentum year after year.

As Dr. Park reflected, “In class, you wonder how to get students’ attention. In the contest, you already have it. The question becomes: how do you best support them so they succeed?”

Looking Ahead

For Dr. Stepien, the ultimate goal is growth and opportunity. “I want this to always be an option for students,” she said. “It gives them exposure to problems they might not encounter in their other classes, and it raises the profile of applied mathematics on campus.”

The UF program shows how a small effort can snowball into something transformative, for students, mentors, and the broader math community. Taboe expands on the possibilities: “One of the things I dreamed of for this contest is that one day, a scientific breakthrough in the mathematical modeling community will arise from a student who was initially motivated by this program at UF.”

As Dr. Park put it: “It’s remarkable how much can happen if you just step back, give students the tools, and let them run with it.”

Written by

COMAP

The Consortium for Mathematics and Its Applications is an award-winning non-profit organization whose mission is to improve mathematics education for students of all ages. Since 1980, COMAP has worked with teachers, students, and business people to create learning environments where mathematics is used to investigate and model real issues in our world.